Article is re-printed from Pilot Magazine with permission by Thom Richard.

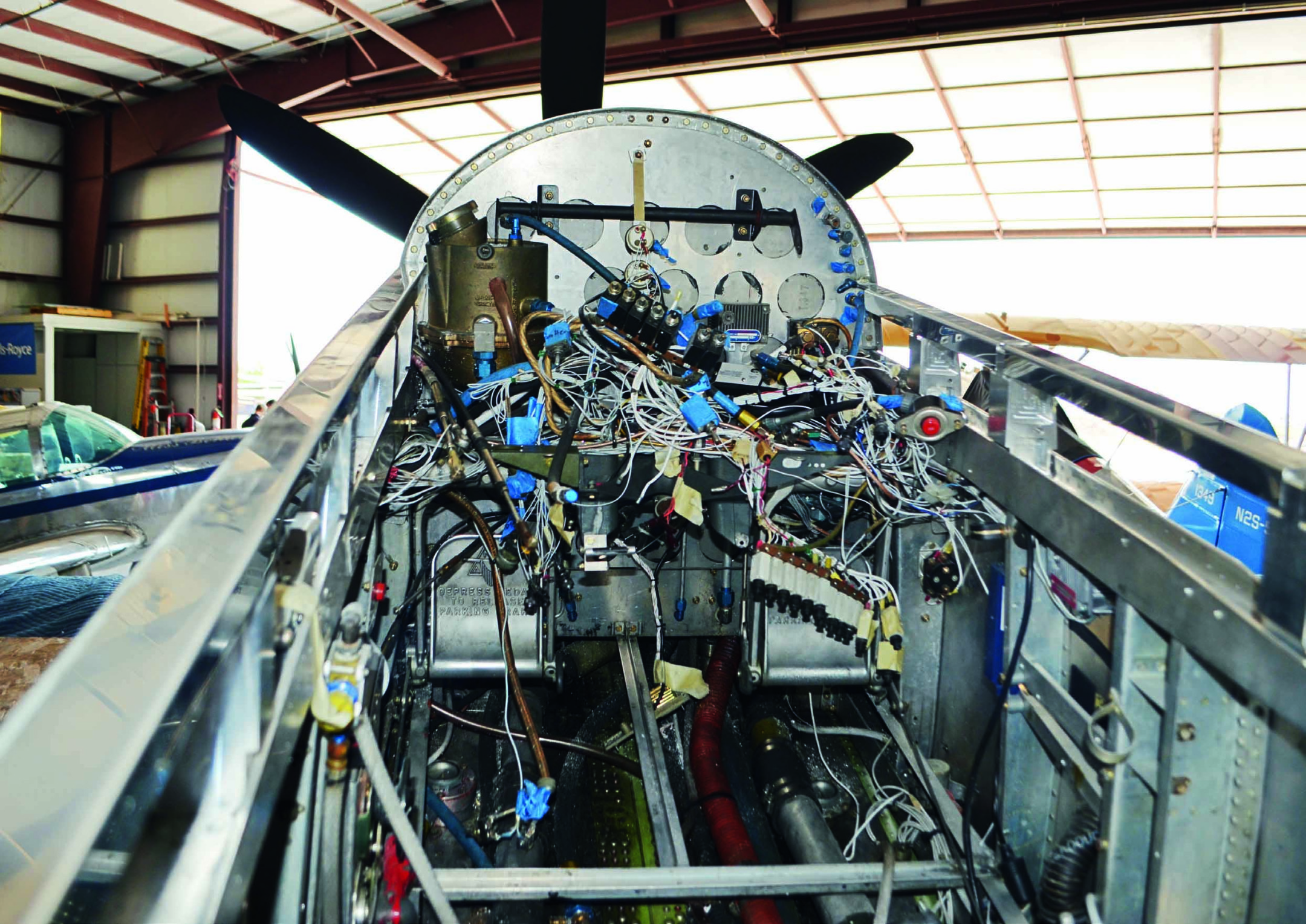

On January 2, 2013 we started on the rebuild of highly-modified P-51 Precious Metal, which would become our entry into the 50th Anniversary National Championship Air Races, held at Reno, Nevada. The idea was to contour the wings with body filler to smooth out the metal skin, install new wing tips, re-work some fairings, upgrade the cooling system, install a ‘choked’ scoop for the radiator intake, fit a new set of trailing-edge strakes and finish overhauling the systems we had not yet touched since we purchased the airplane. She also needed a complete re-wire, new instrument panel installation with a glass cockpit, replacement of the canopy system, and an entirely new race motor with new technology and a new paint scheme. Taking into account all that was ahead, we estimated it taking four to five months of part-time work.

Well, as with all aircraft restoration projects, it always takes twice the time and twice the money. By the time September rolled around, we had put over 6,000 hours of labour into the project in just over eight months. The Griffon is a rare beast. Very few aircraft fly with this fantastic Rolls-Royce powerplant today. The drawback is, of course, that very little modernization has taken place regarding the engine. Everything about top-end Unlimited racing is extreme. Shortcuts don’t work and building experience really pays off. That was proven again in 2013 by both Strega’s and Voodoo’s performance. How the Merlins stay together at the power settings those teams run is nothing short of mind-boggling. Team Precious Metal has a slightly different approach. We are of the school that there is no replacement for displacement. Though the Merlin and the Griffon appear similar at first glance, they are two completely different powerplants. Yes, they are both 60º V12s, but that’s where the similarities end. The Griffon has an extra 589 cubic inches of displacement−an astounding 9.6 litres! Rated takeoff power on the stock motors differs by nearly 1,000hp. The Griffon, with its contra-rotating propellers, is about 700lb heavier. That is certainly a penalty with the installation, as we are forced to fly about eight to ten per cent heavier than the competition. Many people also argue that the propeller installation is not a good design for speed, causes extra induced drag, etc. Perhaps only time will tell, but one of the exciting aspects of racing is the trial and error process. Something to keep in mind is that the fastest propeller-driven aircraft in history have had contra-rotating units, two notable examples being the TU-95 Bear and the Pogo ‘tail sitter’.

Bottom line is that the Griffon/contra-prop combination has yet to realize its full potential. Very little research has been done on the subject, as the aviation industry currently has little need for high-speed contra-prop installations. While a number of postwar aircraft were equipped with this promising setup, they were quickly filed away in history, as the turbojet took over the high-speed end of aviation−an unfortunate fate for such a promising idea.

Proving tests

As we had done some major aerodynamic mods to the aircraft this season, we had to prove the airworthiness of these changes. Simulated race conditions, dive testing, G-load tests (both static and flight loads), as well as the dreaded flutter tests were utilized to determine if the work done resulted in improvements and that the aircraft was also functioning properly. For the flutter tests, you dive the aircraft at high speed and literally strike the stick with a rubber mallet, verifying that the controls don’t ‘buzz’. Upon completion of these flight tests, the determined to be safe by the FAA, the Reno Air Racing Association, and the Unlimited Division. Team Precious Metal was in business.

The paperwork and documentation aspect of racing is a side the general public never sees. Racing airplanes is not just a matter of bloody-knuckle-power and flying in circles. The prep work before the races is a full-time job for a serious crew. Some people are of the opinion that what we do is not only insane, but also closer to suffering from a disease. I disagree. If it was a disease, that makes it sound as if there was a cure. I don’t think there is a cure for race-fever: it’s more of an unbridled obsession.

As we are pushing the envelope with the design of our racer, we’re always looking for weak spots and signs of fatigue and wear. One of those spots, as we were going faster and faster with our airplane, was the canopy structure and design. It was perfectly fine for a low 400s racer, but it’s a different ball game when you exceed 500 mph. I was getting increasingly concerned about the canopy and its structural integrity. I am a person that follows my gut instinct, and when your gut tells you something’s not quite right, it is usually correct. The decision was made to remove the entire structure above the longerons and start over. The design and build of the canopy became, without a doubt, the most difficult and labor-intensive project I had ever been a part of in aviation maintenance. We were also under a serious time crunch, as we had deadlines in June to turn in our flight test data. We did finish and completed the test flights without incident on time, albeit without attending to the paint. The rest of the summer was spent tying up loose ends, completing the paint job, and building a race motor.

A fraught journey

Precious Metal has been plagued with oil leaks her entire career. Her Griffon engine leaks more like a large radial transport motor. Wiping the airplane after each flight has always been necessary, but as we headed towards Dallas, the leaks started getting excessive. We took the cowling off in Cavanugh Air Museum’s hangar on Saturday night, washed the engine down and tightened a few things. Continued to Midland in the morning and a team of volunteers came to help in Ray Hofman’s hangar. I had to blast out of there by midday if I was to make the deadline in Reno that evening. We fixed what we saw, buttoned her up and continued.

Upon reaching New Mexico, the weather turned really bad. After diverting around thunderstorms for an hour, I was forced to set down in Douglas, well short of my intended fuel-stop in Deer Valley, just north of Phoenix. I taxied in to the FBO and the place was a ghost town. No one there on Sundays, apparently. After calling the emergency number on the glass door at the FBO, they explained they had no interest in coming out to fuel me. I could feel the second hand on my wristwatch ticking away the remaining time.

There was another airport ten miles southeast that was supposed to have fuel. I cranked up, and a couple of minutes later taxied in on yet another abandoned ramp. This time, however, I’d found a self-serve fuel pump. A bit like a mirage oasis in the desert, the welcome sight of a credit card station appeared as I came around the corner. I quickly dismounted my steed and ran up to the machine. To my horror, every other letter in the old LCD display was out. If you have ever used one of these antiquated 1980s machines, the user interface is difficult enough if the screen is easy to read… To make things more interesting than they already were, there was a massive thunderstorm coming up from Mexico only a few miles away. It was going to engulf the airport in minutes and with it, my dreams of competing in the 50th Anniversary would be engulfed too.

The Air Racing Gods were smiling down on me this time because I somehow, mostly by luck, managed to make the pump serve me two helpings of 26 gallons each. This was enough to make it to Deer Valley. I leapt into the cockpit and more or less strapped in on the takeoff run with a squall line chasing me down the runway.

The Atlantic aviation crew in Deer Valley was expecting me, and turned me round in ten minutes flat. They knew everything was on the line. They had wipers, someone to clean the windows, fuel and cold drinks. I made a pilot pit stop and was off in record time.

The last leg of the trip to Reno is the longest. The way the airplane is configured, 2.2 hours plus reserve is all the endurance this machine has. The KDVT-KRTS hop usually plans out to be 2.1 hours. However, the weather was not cooperating. Big thunderstorms and the incredibly thick smoke from the Yosemite fires really put the trip in question. The new avionics had worked flawlessly the entire trip, so I made the decision to go IFR. I had no chance of making Reno in one leg if I diverted for the extensive cloud cover and thunderstorms. ATC was very helpful, as always, and they helped me pick my way around the worst downpours. After an hour and a half the weather started getting lighter, I broke out, and for the first time I realized as I sped downhill in to Reno that I was actually going to make it before the deadline.

The whole trip had been in question the entire time, but the relief of knowing I had it made − provided nothing broke in the next twenty minutes−was an amazing experience. I did not let myself dwell on this for long. I needed to keep a cool head and stay professional. Precious Metal is a very unforgiving machine−you cannot let yourself get distracted. I entered the pattern and the Tower welcomed me. Apparently my arrival had been closely monitored. The number of well-wishes from ATC units along the route was astonishing. The wheels touched down at Reno-Stead at 1641 PST−nineteen minutes to spare. I taxied in, shut down and just sat there, completely drained. Mentally and physically I had nothing left, but I was not allowed to remain in this state for long. I became aware that I was being treated to a standing ovation from the crowd that had gathered on the ramp, waiting for my exit from the beast. What a welcome! Reno officials met me by the airplane. They had witnessed me show up on time. I was thrown in to a golf cart and walked in to the registration office three minutes before five o’clock.

Finished fifth — but watch out!

Our engine was weak at best, but we completed all the heat races and placed fifth in the Gold. We did smoke some cams due to some very poor carbide pads we had installed on the rockers−another failed engine improvement attempt. We didn’t know at the time, but we had broken the rings in three cylinders, causing the major oil leakage. The crankcase was pressurizing. We managed to place higher than Precious Metal has ever placed in the field−with a V9! The engine ran smoothly all the way home. I attended a couple of airshows and made it back without any other issues and 36.1 hours on the Hobbs meter.

It’s now 2014, the engine betterment program is well underway, and we’re heading back to Reno again for the 51st. This time we hope to be ready and on site much earlier, with more hair and less stress. Watch out Voodoo, because this time we’ll be bringing a V-12…